Architects rarely have the opportunity to directly deal

with the physical objects of their designs. While others –

creators, artists and designers – work directly with materials,

architects do so abstractly. They represent them and

decide on how they are to be used, but they do not process

and build them themselves. However, all the perceptible

qualities that architects try to convey in their designs ultimately

depend on their manifestation in built form. The

design can underline these material properties, but it also

sets limits. No matter how much architects try to abstract

in their designs and distance themselves from concrete

questions about materials, it is ultimately these that represent

the architectural idea. A sensitive understanding

of materials therefore always conveys more than just the

implementation of design ideas through the means of the

builder. It enables both new interpretations of the relationships

of the parts to the whole and the creation of new

overall relationships, organisational connections and

phenomenological effects.

An understanding of materials is part of the design. The choice of material has an immense influence on the feasibility and functionality of a design. It is the properties of a material that decide for which area of application it is ultimately suitable. It is not for no reason that building materials come from a wide range of materials.

A sensitive approach to materials

at different scales, from architectural detail to urban

design, is therefore always able to convey a contemporary

understanding of our built environment in terms of its

components and their interconnection.

Material ConneXion, New York City (USA), Materials Collection

Design versus choice of materials?

In the discourse of architecture, questions about the role

of materials were often linked to questions about the relationship

of the overall form to the tectonics. Should the

use of materials be subordinated to an overriding formal

idea or follow a «nature» inherent in the materials? Especially

in times of great technological advances and rapid

material developments, this role is questioned. We find ourselves in such a time today.

But instead of engaging

in fruitless arguments and committing to one of the

camps, this article argues for an alternative approach to

the relationship between architecture and materials. By

directly experiencing and looking at materials and their

properties, designers can gain new insights into their formal,

functional, conceptual and expressive potentials.

The direct confrontation with materials points the way to

their targeted use, in the best case also to novel functions

and design possibilities. The guiding principle is the

unique combination of the potential of the material and

the intention of the design. In this way, the architectural

discourse can be led beyond the outdated opposition

between form and tectonic structure as well as beyond

fashionable trends based on the latest material development.

Observation, speculation and experimentation as

an approach can make designers, planners or architects

aware of their intentions in dealing with materials and in

this way promote the design of their drafts. Such an approach

can expand the boundaries of how an idea can

be built, and it can give a whole new twist to the discussion

of material issues.

A distinction between the theory and practice of materials is no longer meaningful, if it ever was. The investigation of the properties of a material leads to questions about the operative logic of dealing with them. Rolling, drawing or pressing, for example, applied to a material such as steel, emphasises its malleability and at the same time represents a fundamental material process. Both material and process in this case are scale-free and can therefore be applied from detail to comprehensive profile systems to the whole building and beyond, and translated into individualised design.

Material experiments

For material studies to gain greater significance in architecture

beyond individual experimentation, a collective

approach is necessary. Universities should

take seriously their role as pioneers and disseminators

of material studies and should provide sufficient

research projects. Material studies have always been an

integral part of architectural training since the days of early modernism Johannes Itten, for example, established

a compulsory basic course at the Bauhaus in which

all students had to experiment with materials and demonstrate

their properties. At the time, this approach shaped

the way a whole generation of architects dealt with materials.

There are currently many efforts to reintegrate

material studies into architectural education. For example,

the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University

has a unique materials collection. The so-called «Materials

Collection» is not just a catalogue of products, but

an active and continuously updated collection of material

and material applications. It also documents material experiments

and research projects of students and teaching

staff at the university. In this way, future generations of

students can refer back to the previous experiments.

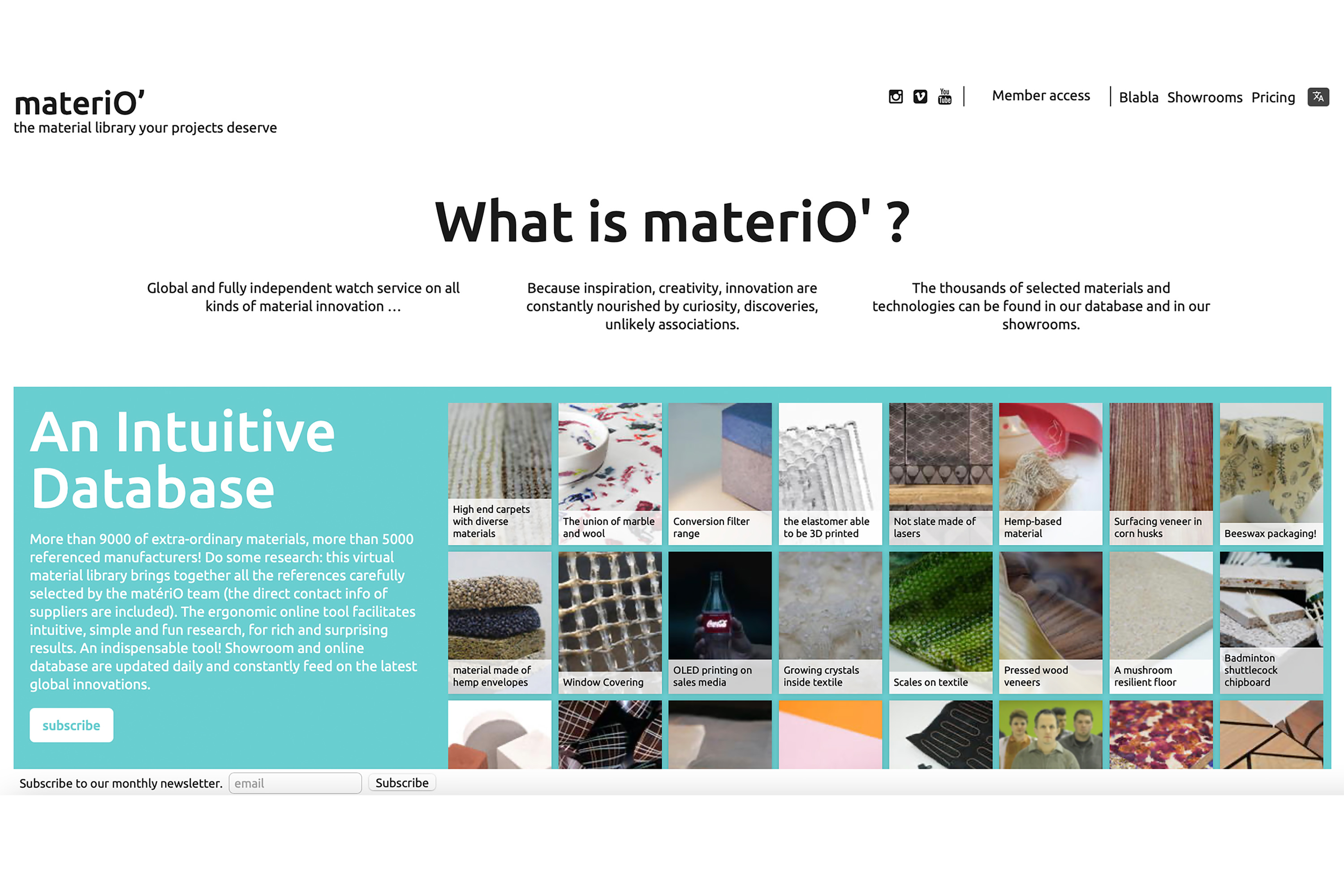

materiO‘, Paris (F), Materials Collection

The

database of the collection is organised in such a way as to

promote an understanding of materials that goes far beyond

the conventional classification into families of materials.

Thus, for example, material is catalogued in the

context of its properties, not only in relation to given applications.

This allows users of the database to discover,

for example, a material for a building fa ade that is normally

used to reduce the reflection of computer screens.

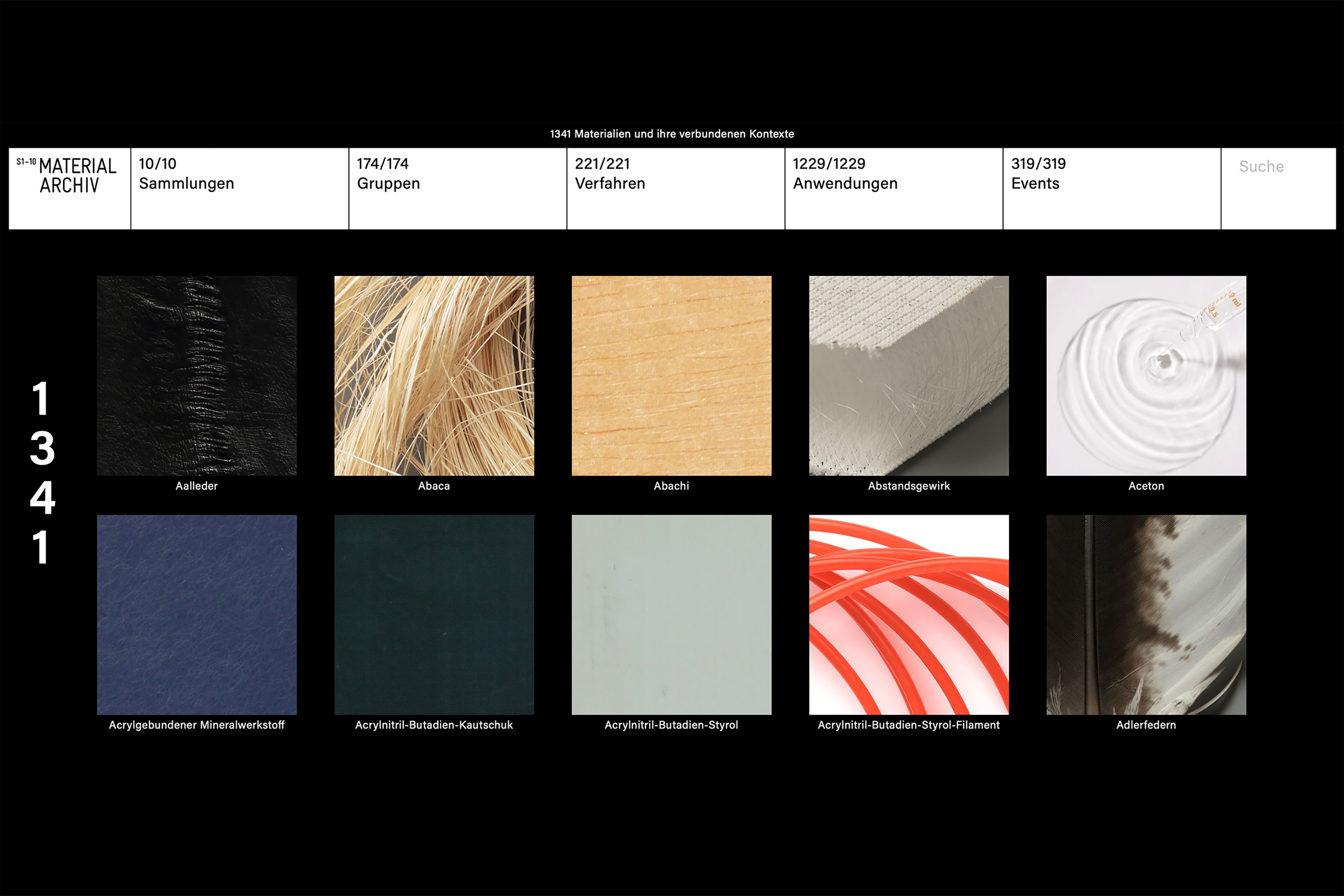

Other institutions outside universities have also recognised

the need for comprehensive material catalogues for

designers. These include the New York-based Material

ConneXion (a source of new and innovative materials

for architects, artists and designers), the in Paris-based

materiO’ and the Swiss database «Material-Archiv», to

name but a few.

New material collections for new design

Today’s design ambitions are based on the desire for

more spatial complexity, a more subtle experience of architecture

and increasingly tailored design solutions. The

search for material innovations is not only for the next

fashionable façade, but also for the urgently needed materials

that express the design ambitions of the 21st century.

It is hardly surprising that the solutions developed

50 years ago, for example, are no longer adequate for

today’s world. The range of materials available to designers

today is also very limited due to outdated classification systems and the lack of integrated research. The

direct engagement of architects with materials through

observation, speculation and experimentation with the

help of new material collections and databases, briefly

outlined here, offers a promising alternative to enable

and determine the design of tomorrow.

materiO‘, online database (materio.com)

Material-Archiv, online database (materialarchiv.ch)

INFO

Dr. Thomas Schröpfer is Professor of Architecture and Sustainable

Design at the Singapore University of Technology and

Design. His book publications have been translated into several

languages and include: Dense + Green Cities: Architecture

as Urban Ecosystem (2020); Dense + Green: Innovative building

Types for Sustainable Urban Architecture (2016); Ecological

Urban Architecture (2012) and Material Design: Informing

Architecture by Materiality (2011). He has received numerous

renowned national and international prizes and awards,

such as The European Centre for Architecture Art Design and

Urban Studies Award, The German Design Award and The President’s

Design Award, Singapore’s highest honour for designers

and design of all disciplines.